A Dissertation on Democracy

Consider this the Cliffs Notes

I began my career as a marine biologist, but a congressional fellowship in 2006 opened my eyes to the need for more people with scientific expertise to engage in the policy process. So I started writing about the relationships between science, politics and culture in books, magazines, newspapers and online where I hosted blogs at Discover, Scientific American and Wired. I co-founded Science Debate, a non-profit organization dedicated to pressing candidates running for office on science policy issues prior to Election Day. And I also began working with PBS on a quirky series about the complex relationships between agriculture and climate change.

My work in academia has centered on the interactions of systems and species, but over time I became increasingly interested in developing a more comprehensive understanding of our role. How humans behave. What we value. Why we make decisions. Fast forward a bit, and now I’m finishing a PhD focused on people. My research explores how senior congressional staff value and prioritize scientific information from various sources.

You see, approaching science related topics in the political arena gets extremely complicated. For example, to wade into nuclear energy, staffers need to balance issues like long-term waste storage with national security concerns during the ongoing energy transition. Climate change decarbonization proposals require a sense of current and future impacts of greenhouse gas emissions and an appreciation of the economic, environmental and social costs of implementation. Emerging areas of concern like Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) involve accepting uncertainty about which people, regions and ecosystems are most affected by the man-made “forever chemicals” now residing in our bodies and environment. In these examples and endless more, legislative decisions will impact the quality of our lives now, and for generations to come.

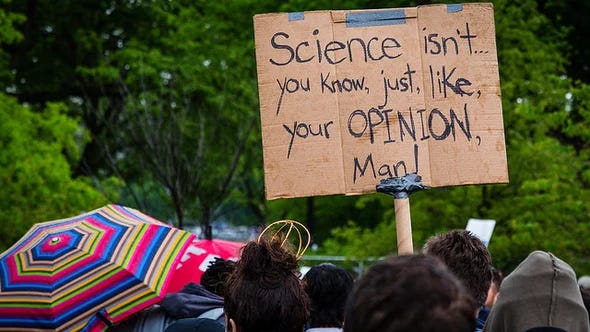

In schools, we teach science through the lens of single subjects - biology, chemistry, and physics - but it’s the ways they interact with economics, psychology, and more, that shape our world. Ultimately, science is related to every significant challenge we face. It’s written into the agricultural policies that sustain us. It ensures we have clean drinking water and enough energy to keep the lights on. At is core, science is fundamental to our health, safety, and future.

As I now write my dissertation, I want to share what I’m learning beyond academic publications where findings are usually stuck behind a paywall. If scientists are to have a meaningful positive impact in society, we must continue to adapt to the changing media environment, work to be more inclusive and find new ways to actively connect with communities outside of the ivory towers.

Further, for democracy to succeed, it’s vital that more Americans understand how Congress works. The “politics” we see on cable news and across social media have become modern sport and spectacle, intended to elicit clicks, shares and outrage. It doesn’t reflect the reality and nuance of what actually takes place behind the scenes in Washington, DC. Not by a long shot.

And that’s what to expect from Unelected Representative in 2023. Thanks for reading, sharing and subscribing. And Happy New Year!

Hello, Sheril,

This looks like it will be an intriguing set of essays, given the wide and jaundiced view many of us have towards the administrative state and the "deep state".

If you plan to stay focused on the science knowledge vs. legislative policy impact, that is fine. But I hope you might also expand to consider:

1) How to make these "hidden" folks more "accountable", either directly by bringing more of them into the limelight, or via greater association with the legislator that they are hired to support.

2) What interactions do or should occur across the institutions between legislative staff with the executive agency staffs; and/or vice versa? And maybe even occasionally judicial staffers?

Just so you know, I came upon this substack via Razib Kahn's Unsupervised Leaning substack (email).